Saul Leiter: Portfolio Example

By Alice Li

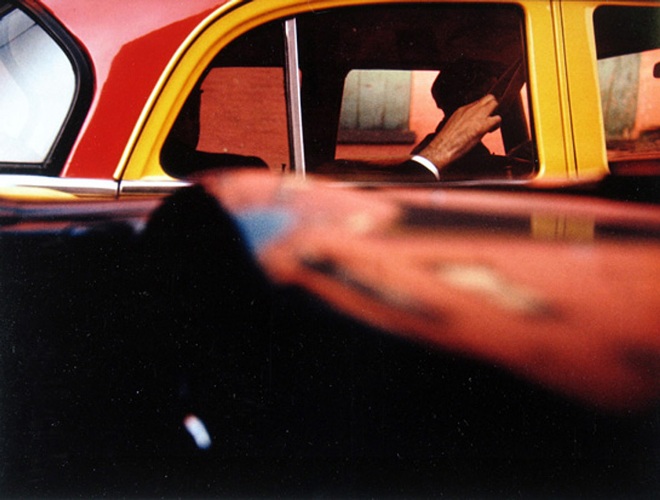

Taxi, Leiter.

Taxi, Leiter.

I think Picasso once said that he wanted to use green in a painting but since he didn’t have it he used red. Perfection is not something I admire. A touch of confusion is a desirable ingredient.1

Saul Leiter

Saul Leiter’s street photography has often been associated with the abstract expressionist movement. What made his work stand apart from that of his contemporaries was his approach and subject matter. Leiter shot scenes of the city and its denizens, often from unusual angles and vantage points. Many of his photographs experimented with color, and they were often oblique, creating abstracted compositions. His photos discover the beauty of the city in brief, fragmented moments. The fragmentation, along with the distance from the subject, is a hallmark of Leiter’s photography. Leiter deliberately sought out disorienting images in order to provide an alternative way of seeing, of framing events and interpreting the reality of the city the people in his photographs interacted with.2 His subject, unlike many of his contemporaries, is the urban visual experience – not people on the street, but what they see and experience.

Born and raised in Pittsburgh, Leiter was one of four children in a highly religious family. His father was a prominent rabbi and Talmudic scholar and made no pains to hide the fact he wanted the same for his three sons. Leiter “grew up in a world where [he] studied what God wanted.” Much to his father’s displeasure, Leiter turned away from that world, instead choosing to pursue painting and, later, photography. His only ally was his sister, who he felt was a talented painter. She later became schizophrenic.

“My father thought photography was done by lowlifes. My family was very unhappy about my becoming a photographer—profoundly and deeply unhappy.” – Saul Leiter 3

Even in the face of his rigid upbringing and his parent’s disapproval of his chosen vocation, Leiter moved to New York in 1946 to become a painter. This rebellion would later make multiple recurrences throughout Leiter’s career as a painter and photographer. “It should be mentioned that in my life I constantly heard ‘You can’t do this. You should not do that.’ Leiter said in an interview with Sam Stourdze. “Yet I did so many things I was told I couldn’t do.” In 1947, he discovered street photography by visiting the exhibition of Henri Cartier-Bresson at MoMA. He photographed the streets of New York in black and white and in the following year became interested in color. Leiter worked for thirty years for prestigious magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar, Esquire, Elle and British Vogue.4

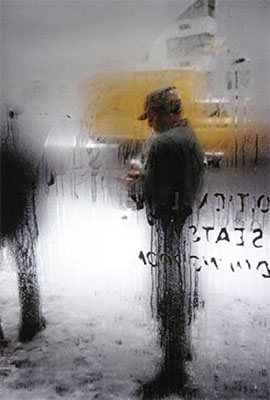

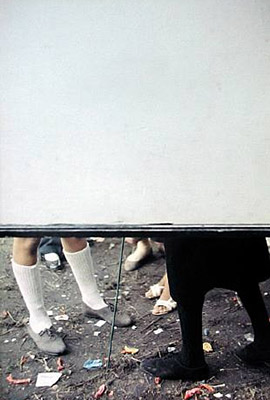

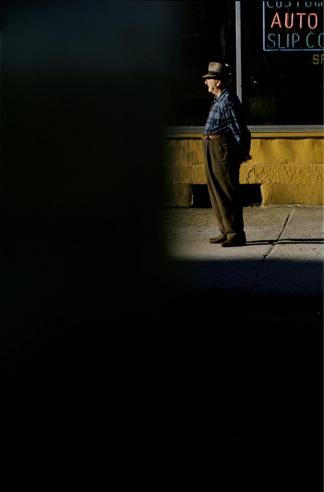

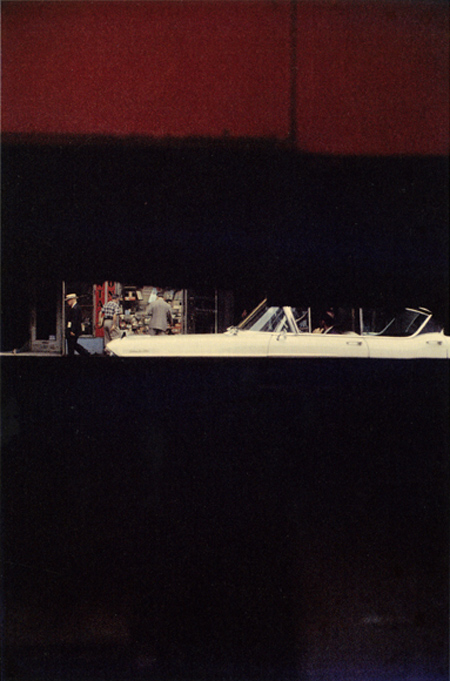

Leiter once said in an interview that he was not religious and he rarely, if ever, cited his Jewish upbringing as a source of influence in his work. This comes as little surprise given the tense relationship with his parents regarding his pursuit of painting and photography. For all intents and purposes, Leiter was an outsider in his family. Although Leiter was able to leave behind the expectations of becoming a rabbi by rebelling against his father, it’s likely that he was impacted by the disconnect he felt as a result of his Jewish heritage. Besides his sister, Leiter received no support from his parents or other siblings in his pursuit of the arts. This quality of being an outsider would later inform Leiter’s images in New York – many of his photographs explored the theme of belonging by visualizing the way residents interacted with the metropolitan space. Leiter often shoots through architectural elements of the city to depict his subjects’ interactions with urban space. Foreground elements tend to frame people within their urban contexts. These objects also create a layer of distance, emphasizing the atomization of individuals, despite the city’s density, as seen in the image “Auto” to the right.

Leiter once said in an interview that he was not religious and he rarely, if ever, cited his Jewish upbringing as a source of influence in his work. This comes as little surprise given the tense relationship with his parents regarding his pursuit of painting and photography. For all intents and purposes, Leiter was an outsider in his family. Although Leiter was able to leave behind the expectations of becoming a rabbi by rebelling against his father, it’s likely that he was impacted by the disconnect he felt as a result of his Jewish heritage. Besides his sister, Leiter received no support from his parents or other siblings in his pursuit of the arts. This quality of being an outsider would later inform Leiter’s images in New York – many of his photographs explored the theme of belonging by visualizing the way residents interacted with the metropolitan space. Leiter often shoots through architectural elements of the city to depict his subjects’ interactions with urban space. Foreground elements tend to frame people within their urban contexts. These objects also create a layer of distance, emphasizing the atomization of individuals, despite the city’s density, as seen in the image “Auto” to the right.

Like many of his Jewish contemporaries, Leiter was embarking on photography at a time when the world was still reeling from World War II and Jews were still struggling to come to terms with the atrocities from the Holocaust. In that context, Leiter’s rebellion from his family and his attempt to create a new sense of belonging for himself in a decidedly secular, cosmopolitan environment were all the more poignant. We can understand his parents’ dismay, when Leiter abandoned religious tradition and practice. And we can understand how the rejection of tradition may have contributed to Leiter’s sensitivity to his new, cosmopolitan context. Taking pictures was a way for him to channel that sensitivity and read the city’s codes. Max Kozloff, an American Art Historian, argued in his essay “Jewish Sensibility and the Photography of New York” that the images of New York by Jewish photographers during the middle century tended to reveal a unique social tension absent in the work of their non-Jewish colleagues.

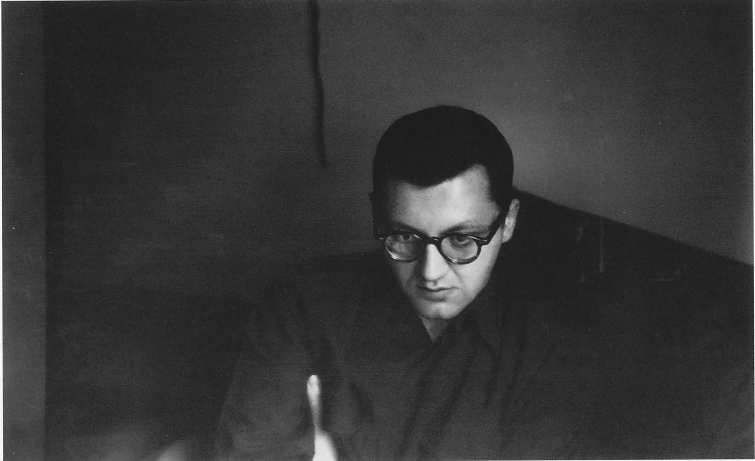

Self-portrait, Leiter circa 1950.

Self-portrait, Leiter circa 1950.

“What [Jewish photographers] saw was an array of peoples existing within the weakening gravitational pull of their ethnic and sexual cultures, but still at hazard in the common culture, which had not proven that it could sustain them. In other words, most New Yorkers carried on, normatively, in a mode of displacement. We may walk the street apparently in one physical current, yet also at psychological angels to each other.” – Max KozloffAn inordinate amount of photographers doing street photography in New York during the mid-1900’s were Jewish. Not only were they Jewish, but there was, as Kozloff seemed to be arguing, something inherently different in the way they were capturing the city. “It is their improvised exchange with their subjects, not a kit of fixed and essential attributes that defines their work,” Kozloff said. Jewish photographers frequently used their images as a way to interrogate issues of cultural assimilation, American class structure and the interactions with and in the metropolitan space of New York City. Their perception of the city and the question of space and belonging had been irrevocably altered by their own cultural displacement from the Holocaust.

This ‘improvised exchange’ mentioned by Kozloff is evident in Leiter’s own work. According to Lisa Hostetler, “Leiter’s aesthetic philosophy was a firm belief in art as an activity rather than a product – a verb rather than a noun.” In many of Leiter’s photographs, the slightest adjustment in the photographer’s position or a split-second change in timing would result in a radically different image. Such seeming arbitrariness lent the photographs a quality of the ephemeral. More importantly, though, it allowed viewers to become intimate participants in the interaction between the subject and the inhabited space captured.

For years many of his images remained in slide form, stored away in boxes, unseen by the general public.5 Only now is Leiter beginning to receive recognition for his photographs.

Pink Umbrella, Leiter.

Pink Umbrella, Leiter.

Leiter made a point of stressing in an interview once that when he took photographs he didn’t preplan, or in his words: “As a rule I prefer to see what happens.”6 This may seem difficult to believe given the cinematic quality of his photographs, but so often his subjects are caught in a fleeting moment of movement. And so, in true Leiter style, I decided to take photographs with as little calculation as possible.

I don’t have a philosophy. I have a camera. I look into the camera and take pictures. My photographs are the tiniest part of what I see that could be photographed. They are fragments of endless possibilities.7

Saul Leiter

Snow, Leiter.

Snow, Leiter. Shopper, Li.

Shopper, Li.

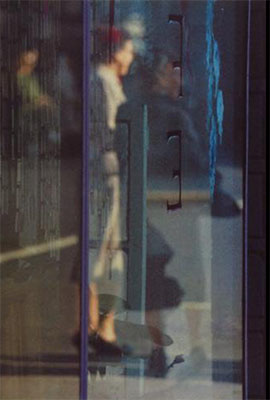

While spontaneity was to be my philosophy for the weekend, I knew before embarking on my excursion that I wanted to emulate certain characteristics from Leiter’s photographs. Leiter’s camera provided an alternative way of seeing, of framing events and interpreting reality.8 He did this by taking great pains to remain distant from the subject of his images. Although Miles Orvell points out in his book American Photography that “the image carries with it an inescapable element of a point of view, a subjectivity,”9 Leiter tried to keep his presence as a photographer as unobtrusive as possible. He used what was around him to conceal his presence while introducing an intriguing compositional structure of his photographs. Such structures include shooting through windows, using framing and shooting from low and high angles to get a different perspective.

Initially I wanted to take photos on my iPhone. I figured it would be easier for me to conceal the fact I was taking a photograph under the guise of perusing my phone. After several attempts I noticed that the photo quality on my phone was, ironically enough, too crisp for the aesthetic I was going for. When Leiter first began experimenting with color photography he often used poor quality or outdated film, which resulted in an unusual range of colors.10 I quickly aborted use of my phone and instead turned towards disposable cameras.

I bought two disposable cameras from Walgreens and on Saturday and Sunday took pictures wherever I was and thought I could avoid being noticed. I ended up not going to 4th Street in Berkeley. Instead, I simply went about doing errands and whatever else felt natural. I thought it would be better to bring my camera with me – this process allowed me to see routes I normally took with a completely different mindset by studying more closely how those around me were interacting with the urban space.

For instance, when I went to the repair shop to pick up my bicycle I took pictures of pedestrians through the windows, as seen in the image to the left. I photographed reflections of people in mirrors while walking down Valencia Street. On the BART, I overtly took a snapshot of passengers waiting for the next train through the window. Unfortunately, given the disposable cameras inability to zoom in, I was far from stealthy.

That proved to be the most challenging aspect of taking photographs in Leiter’s style. A big component of his images is his utter lack of presence as a photographer. I didn’t want to alert my subjects of the fact I was taking a photograph. I feared this would cause them to act unnatural when the main purpose was to capture them in their natural surroundings. There were moments when I spotted a photo opportunity but couldn’t find a way to take a picture without being obvious.

I attempted to find ideal ways of framing individuals – doors, through blinds, windows, etc. At home I cracked open my window a little and used the bottom of the window to obstruct part of the lens. I photographed people below walking or biking. Leiter often captured his subjects at a lower angle, using the height advantage to create a new perspective. Similarly, Leiter’s way of seeing and working with reflections and mirrors would add layer after layer of complexity.11 Many of my own photographs are of my subject’s reflection. Additionally, I tried to keep my photographs vertical to match Leiter’s tendency to take vertical pictures. When questioned by an interviewer, Leiter did not assign much meaning to this habit. He simply responded, “Just call me Mr. Vertical.”12

Below are the two locations where I took pictures over the weekend. I choose these locations because both streets typically boast of high pedestrian traffic and so I would have a better chance of capturing the way that people interacted with their surroundings.

Missing Link Bicycle Cooperative, Shattuck Avenue, Berkeley

View Larger Map

Valencia Street, Mission

View Larger Map

Image to the left: Through Boards, Leiter.

Image to the left: Through Boards, Leiter.

It’s quite possible that my work represents a search for beauty in the most prosaic and ordinary places. One doesn’t have to be in some faraway dreamland in order to find beauty.13

Saul Leiter

Leiter’s early compilations of street photography are lush with color, texture and layers. For example, the photograph on the cover of Early Color, a collection of Leiter’s street photographs, embraces these characteristics. The subject in this image is the thin strip of the city: the three men and the white car. Two thick black bands frame the strip, the upper half interrupted with a splash of bold crimson. The red band itself is split with a vertical black stripe about two-thirds of the way along its length. Leiter’s disjointed framing, as well as his ability to make color the subject of his photographs, are what lend his photographs a whimsical and unique nature.

He took hundreds of street photographs and kept them mainly to himself, due to the expense of developing color film. Consequently, it wasn’t until early 2000 that Leiter began receiving recognition for his contribution to color photography. Given Leiter’s use of expired color film, partly due to financial reasons and partly in the name of experimentation, a lot of his color photographs have a slightly nostalgic quality. To obtain that nostalgic quality, I wanted to go through the process of having the film processed instead of adding filter on my iPhone photos. The treatment of digital photography versus print photography is fundamentally different. I feel like there is less thought given to taken photographs with a camera phone. If you don’t like the image, all you have to do is delete and take another one. With a disposable camera, you’re forced to really take your time and look through the small lens, gauging for the right moment when to take a picture and forced to come to terms with what you’re looking at. It’s that kind of thoughtfulness that is evident in Leiter’s own images.

Bicycles, Li.

Bicycles, Li.

Very little is straightforward in Leiter’s photography. His color work rarely establishes intimacy with his subjects. His work is not up close and personal – the viewer is kept at a distance. The cumulative effect is of a distinctly expressive vision of the city, a vision that is not wide and expansive, but indirect and fragmented. Unlike Helen Levitt, who also experimented with color street photography, Leiter was capturing the interacting between his subject and the urban surrounding. Levitt focused more heavily on the subject. As Kozloff said in his essay:

“Whether the public space of the city is inherently sharable, and there no big deal, or whether there exist partitions, invisible yet strongly felt: such an issue is revolved in an important sector of New York photography. A photographer’s instinctive reaction to the sociality of metropolitan space is determined essentially through the placement of figures.”

There still seemed to exist the question of just who exactly the urban space, teeming with a varied – not just Jewish – diaspora, belonged to. Leiter would have understood this notion very deeply. He was, after all, an outsider in his own family. He was not originally from New York. And as a Jewish man, the cultural impact of the Holocaust must have been very profound. In his photographs, the way that people interacted with their environment would have gotten to the very heart of ‘belonging.’ I decided to base my photo selection off that very claim, choosing images that offered brief glimpses of the city and its denizens.

A Pair of Three, Li.

A Pair of Three, Li.

Looking back at my photos, there are a lot of details I missed when taking them. One is the number of symmetry in my photographs. Almost every photo included in my selection has a form of symmetry – whether it is the form of two people, in a person and their shadow, in the number of people in a given frame. For example, in the photograph above there is the symmetry of three men sitting behind the window and three sitting outside. In both rows, the men on the edge are preoccupied whereas the men in the center are both aware of and acknowledge the photographer’s presence.

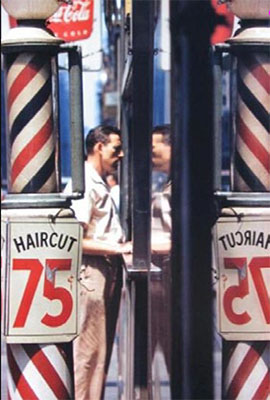

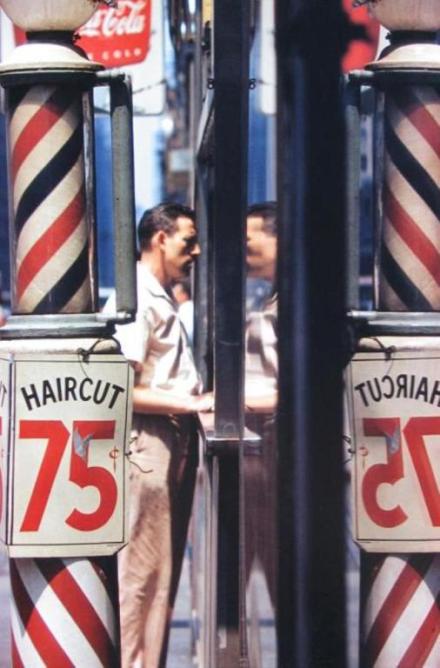

I went through Leiter’s photographs to see whether this was an aspect I had missed in his own photo selections and surely enough, there is form of symmetry evident in a number of his photographs. The photograph on the right below, “Haircut,” is a strong example of symmetry in Leiter’s body of work. More importantly though is the portrayal of a particular subject (or in my case multiple subjects) interacting with their surroundings. The man in “Haircut” is gazing through the windows and gauging his own need for a haircut. Levitt, on the other hand, got close-up and personal with her subjects to the point where their interaction with her as the photographer plays into the image itself. In “Photo Booth,” depicted bottom left, the little girl is clearly looking at Levitt. The disdainful look she shoots the camera suggests a conversation is occurring between both the photographer and her subject. Leiter acted more like an anthropologist, remaining a safe distance away while studying how people interacted and, similarly, were influenced by their direct surroundings. The result is a strange paradox of Leiter looking at people looking at the world. Despite the physical distance from the subject, the narrowed field of vision provides a surprisingly profound look into that person’s perspective.

Haircut, Leiter.

Haircut, Leiter. Photo Booth, Helen Levitt.

Photo Booth, Helen Levitt. Mannequins, Li.

Mannequins, Li.

I’m supposed to be a pioneer in color. I didn’t know I was a pioneer, but I’ve been told I’m a pioneer. I’ll just go ahead and be a pioneer!14

Saul Leiter

Through this exercise, I came away with a greater understanding of Leiter’s perspective. His appreciation for capturing the city in fragmented, brief moments from strange angles, vantage points, and using windows, reflections and frames adds a further dimension to the image. Things are not as obvious upon first glance. By being forced to confront the image through an obstruction or hidden vantage point, the viewer comes away from the photograph with both a literal and metaphorical different point of view. Furthermore, my experience of seeing and experiencing the city when taking my own photographs became incredibly impressed by the interactions I witnessed between my subjects and their surroundings.

Along with Leiter’s talent for taking photographs from a diverse range of perspectives, the use of color in his images is unparalleled amongst his contemporaries save for perhaps Helen Levitt. In many ways, the subject of his photographs is color. Although his color photography did not garner attention until these past two decades, Leiter made a significant contribution to color street photography.

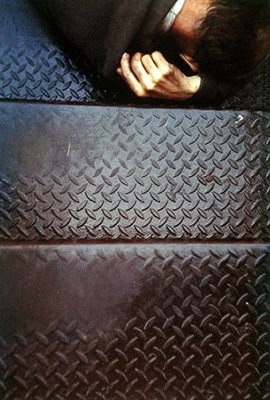

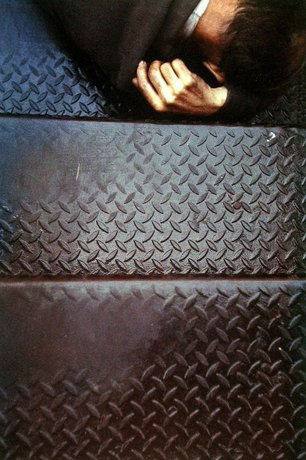

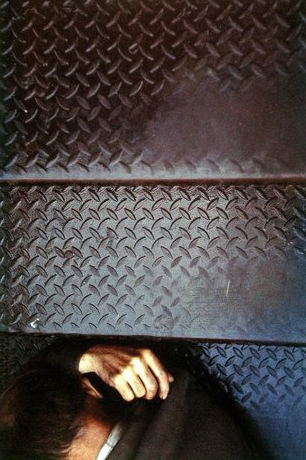

Tanager Stairs, Leiter.

Tanager Stairs, Leiter. Tanager Stairs reversed.

Tanager Stairs reversed.

There is a connection to the subjects in the photograph, no matter how seemingly “distant” the photographer may appear. Orvell points out that in order to really understand a photograph, one of the characteristics of an image to keep in mind is the aesthetic composition of the photograph.15 Leiter has a talent for finding and/or creating structure – the viewer’s eye is immediately drawn to the subject of his photograph and the subject’s own observation of urban space, whether is be a man staring into the window of a barber shop or a thin strip of a street, framed by a board and a red canopy. The composition is just as important as the subject when it comes to the narrative of the photo. For instance, the photograph of the man asleep on the stairs of Tanagers is a perfect example of compositional structure. The eye is drawn to the man’s head at the upper right corner of the photograph and despite the 2D nature of the photograph the stairs are clearly descending down. The man himself is both physically and literally on the lowest step of the staircase.

Additionally, instead of photographing the man’s entire body Leiter only focuses on his head and the arm cradling it. As a presence, the man actually takes up very little space in the photograph, assigned to the periphery and even then given very little room to negotiate with the otherwise negative space of the stairs. Leiter has achieved not only to capture the way this man, undoubtedly down on his luck, interacts with the staircase but also with society at large, most probably viewed as somebody who has little to contribute and thus resigned to the edges of society. A second perspective comes into play here as well. Leiter could have arranged the photograph so that the man was on the bottom instead of the top, placing even greater emphasis on the man’s perspective. Instead, he took the picture from the perspective of somebody walking down the stairs and coming upon the man’s prone figure lying there. The second perspective, in other words, is you.

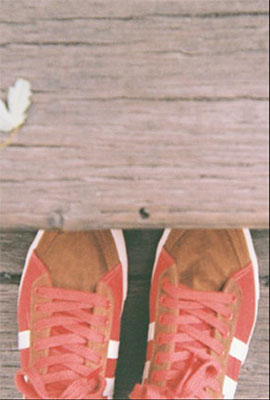

Shoes, Li.

Chalk, Li.

Hostetler pointed out that viewing Leiter’s work, along with Jewish photographers at the time, is meant to be a dynamic activity. Leiter encourages investment in his photographs by forcing the viewer to really question the image in front of them. Jewish photographers at the time dealt a lot with existentialism, a theme that had infiltrated American culture in the years after World War II. While Leiter’s work certainly carries an element of existential questioning and introspection, his main focus was on the process of taking photographs. As mentioned previously, Leiter believed in art as an activity rather than a product. By doing so, he was able to highlight the fleeting nature of perception evident in his photographs.

As stated in my thesis, Leiter captures the interaction between urban space and the people that exist in it. The subjects of his photographs are not necessarily the people themselves, but their perspective and their experience of the city around them. By doing so, he was able to draw the viewer’s attention to hidden sides of the city and capture fleeting symbiotic relationship of a person being influenced, and in turn exerting influence on, their surroundings.

Leiter once said in an interview, “I don’t attach as much importance to sequencing as other people do. To me the content is more important.”16 That being said, sequencing can help provide a kind of narrative arc to a collection of photos and I wanted to highlight the juxtaposition between Leiter’s photos and mine. I selected ten photos from Leiter’s street photography collection and ten photos from mine that I felt mirrored or captured a similar theme to a corresponding Leiter image. It was important to emphasize that although both Leiter and I were seeking to capture the relationship between an individual and the urban space around them, ultimately the two urban spaces we were operating in differ. This difference provides an interesting look into not only how people interact with their environment, but how different and similar those interactions can be depending on the environment.

The series begins with a shot taken by Leiter of a window and through that window tree branches. Below that is an image taken by me of a tree branch and in the distance, out of focus, the street. I wanted to establish straightaway that the subject of a photo, at least within this series, is not always of a person but rather the space that exists around them. The subsequent images begin gradually introducing human subjects into the frame, but never in a straight-forward manner. The subjects are frequently pushed to the periphery of an image or are captured through obstructions such as windows or mirrors. Gradually, despite the fragmented moments in each individual picture, a mosaic of the city and its denizens begins to emerge.

Refer below to view photo slideshows. In order to view the images as intended, first click on the Leiter slideshow and then the Li slideshow to see corresponding images.

1 Brierly, Dean. Photographers Speak, “Saul Leiter: The Quiet Iconoclast.” <http://photographyinterviews.blogspot.com/2009/04/saul-leiter-quiet-iconoclast-saul.html>

2 Bunyan, Marcus. Art Blat, “Exhibition: ‘Saul Leiter Retrospective’ at the House of Photography at Deichtorhallen Hamburg.” <http://artblart.com/tag/saul-leiter-through-boards/>

3 Brierly, Dean. Photographers Speak, “Saul Leiter: The Quiet Iconoclast.” <http://photographyinterviews.blogspot.com/2009/04/saul-leiter-quiet-iconoclast-saul.html>

4 Bunyan, Marcus. Art Blat, “Exhibition: ‘Saul Leiter Retrospective’ at the House of Photography at Deichtorhallen Hamburg.” <http://artblart.com/tag/saul-leiter-through-boards/>

5 Photo Slaves, “Saul Leiter.” <http://photoslaves.com/saul-leiter/>

6 Brierly, Dean. Photographers Speak, “Saul Leiter: The Quiet Iconoclast.” <http://photographyinterviews.blogspot.com/2009/04/saul-leiter-quiet-iconoclast-saul.html>

7 Brierly, Dean. Photographers Speak, “Saul Leiter: The Quiet Iconoclast.” <http://photographyinterviews.blogspot.com/2009/04/saul-leiter-quiet-iconoclast-saul.html>

8 Bunyan, Marcus. Art Blat, “Exhibition: ‘Saul Leiter Retrospective’ at the House of Photography at Deichtorhallen Hamburg.” <http://artblart.com/tag/saul-leiter-through-boards/>

9 Orvell, Miles. Google Books, “American Photography.” <Pages 13-15>

10 Casper, Jim. Lens Culture, “Saul Leiter: 1950-60s color and black-and-white.” <http://www.lensculture.com/leiter.html>

11 Colberg, Joerg. Conscientious, “Review: Saul Leiter.” <http://jmcolberg.com/weblog/2012/02/review_saul_leiter_kehrer/>

12 Brierly, Dean. Photographers Speak, “Saul Leiter: The Quiet Iconoclast.” <http://photographyinterviews.blogspot.com/2009/04/saul-leiter-quiet-iconoclast-saul.html>

13 Brierly, Dean. Photographers Speak, “Saul Leiter: The Quiet Iconoclast.” <http://photographyinterviews.blogspot.com/2009/04/saul-leiter-quiet-iconoclast-saul.html>

14 Bicker, Phil. Time LightBox, “A Casual Conversation with Saul Leiter.” <http://lightbox.time.com/2013/02/19/a-casual-conversation-with-saul-leiter/#1>

15 Orvell, Miles. Google Books, “American Photography.” <Pages 13-15>

16 Bicker, Phil. Time LightBox, “A Casual Conversation with Saul Leiter.” <http://lightbox.time.com/2013/02/19/a-casual-conversation-with-saul-leiter/#1>

Images

Leach, Thomas. In No Great Hurry, “Saul at home.” <http://www.innogreathurry.com/InNoGreatHurry/AbouttheFilm.html>

Leiter, Saul. Jackson Fine Art, “Auto.” <http://www.jacksonfineart.com/Saul-Leiter-5467.html>

Leiter, Saul. Jackson Fine Art, “Canopy.” <http://www.jacksonfineart.com/Saul-Leiter-481.html>

Leiter, Saul. Gallery 51, “Footprints.” <http://www.gallery51.com/index.php?navigatieid=9&fotograafid=15>

Leiter, Saul. Jackson Fine Art, “Foot on El.” <http://www.jacksonfineart.com/Saul-Leiter-485.html>

Leiter, Saul. Jackson Fine Art, “Haircut.” <http://www.jacksonfineart.com/Saul-Leiter-486.html>

Leiter, Saul. Gallery 51, “Harlem.” <http://www.gallery51.com/index.php?navigatieid=9&fotograafid=15>

Leiter, Saul. Gallery 51, “Kutztown.” <http://www.gallery51.com/index.php?navigatieid=9&fotograafid=15>

Leiter, Saul. Gallery 51, “Mondrian Worker.” <http://www.gallery51.com/index.php?navigatieid=9&fotograafid=15>

Leiter, Saul. M+B Exhibition, “On the El.” <http://www.mbart.com/exhibitions/_2,573,,18/>

Leiter, Saul. M+B Exhibition, “Phone Call.” <http://www.mbart.com/artists/_Saul%20Leiter/_other%20works/_575,18/>

Leiter, Saul. M+B Exhibition, “Pink Umbrella.” <http://www.mbart.com/artists/_Saul%20Leiter/_other%20works/_594,0/>

Leiter, Saul. Jackson Fine Art, “Shopper.” <http://www.jacksonfineart.com/Saul-Leiter-495.html>

Leiter, Saul. Jackson Fine Art, “Sky Light.” <http://www.jacksonfineart.com/Saul-Leiter-5439.html>

Leiter, Saul. Jackson Fine Art, “Snow.” <http://www.jacksonfineart.com/Saul-Leiter-497.html>

Leiter, Saul. Daily Serving, “Straw Hat.” <http://dailyserving.com/2012/04/saul-leiter-retrospective-at-hamburgs-deichtorhallen/leiter_man_with_straw_hat_01/>

Leiter, Saul. Gallery 51, “Tanager Stairs.” <http://www.gallery51.com/index.php?navigatieid=9&fotograafid=15>

Leiter, Saul. Gallery 51, “Taxi.” <http://www.gallery51.com/index.php?navigatieid=9&fotograafid=15>

Leiter, Saul. Jackson Fine Art, “Through Boards.” <http://www.jacksonfineart.com/Saul-Leiter-500.html>

Leiter, Saul. Gallery 51, “Walking.” <http://www.gallery51.com/index.php?navigatieid=9&fotograafid=15>

Levitt, Helen. Laurence Miller Gallery, “Phone Booth.” <http://www.laurencemillergallery.com/levitt_just_kids.html>

Remaining photographs courtesy of Alice Li.

Maps

Courtesy of Google Maps.

Research Materials

Bicker, Phil. Time LightBox, “A Casual Conversation with Saul Leiter.” <http://lightbox.time.com/2013/02/19/a-casual-conversation-with-saul-leiter/#1>

Brierly, Dean. Photographers Speak, “Saul Leiter: The Quiet Iconoclast.” <http://photographyinterviews.blogspot.com/2009/04/saul-leiter-quiet-iconoclast-saul.html>

Bunyan, Marcus. Art Blat, “Exhibition: ‘Saul Leiter Retrospective’ at the House of Photography at Deichtorhallen Hamburg.” <http://artblart.com/tag/saul-leiter-through-boards/>

Casper, Jim. Lens Culture, “Saul Leiter: 1950-60s color and black-and-white.” <http://www.lensculture.com/leiter.html>

Colberg, Joerg. Conscientious, “Review: Saul Leiter.” <http://jmcolberg.com/weblog/2012/02/review_saul_leiter_kehrer/>

Hostetler, Lisa. “Street Seen: The Psychological Gesture in American Photography, 1940-1959.” Milwaukee: Prestel, 2009.

Kozloff, Max. “Jewish Sensibility and the Photography of New York.” Jewish Museum Press/Yale University Press, 2002.

Orvell, Miles. Google Books, “American Photography.” <Pages 13-15>

Photo Slaves, “Saul Leiter.” <http://photoslaves.com/saul-leiter/>

Video

Leach, Thomas. In No Great Hurry, “Trailer.” <http://www.innogreathurry.com/InNoGreatHurry/Trailer.html>